Frank Heaney – Eulogy

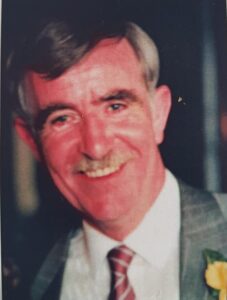

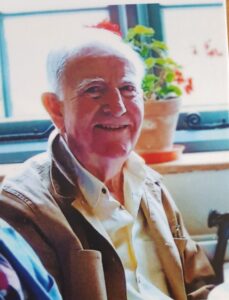

Born in Dagenham on 7 September 1935, Frank was the middle child of three boys, Jack, himself, and Colin, born to Patrick and Marie, two good Belfast Catholics – although according to Frank, a direct line existed down from the 10th century Irish King, Brian Boru.

He was four when war broke out in September 1939, and spent the war years back and forth between Dagenham and West Belfast, staying with relatives in a two-up, two-down Victorian terrace in Benares Street – the children sleeping two or more to a bed upstairs, the parents in an alcove under the stairs. But, as he was keen to point out, they never thought of themselves as poor.

School was a very different place in those days, corporal punishment the norm, a situation that his granddaughter Gabriella, herself a teacher, would dearly love to get back to – although perhaps not to the extent that the nuns who taught Frank employed it, using a ruler across the back of the hand for the heinous crime of singing out of tune.

That’s not to say it didn’t bring out the best in them at times. One teacher was so fond of using the cane that it snapped – although it’s unclear whether it was on Frank’s own backside. A cause for celebration, nonetheless, you’d think. But, no, the kids clubbed together and bought him a new one – suffice to say that particular teacher never caned them again.

I’m sure Frank excelled at school and in his examinations, although we never heard about it. What we did hear about was how it was possible to climb onto the roof of the school toilets and lie in wait, then reach in and pull the chain while some unsuspecting victim was in the middle of proceedings – he was eighty-five the last time he told the story and he laughed until the tears ran down his face.

He also remembered his days as an altar boy with fondness, not so much the spiritual side of things, but dripping hot candle wax onto the heads of the smaller boys in front, a delicate technique that took skill and practice so as not to topple the whole candle and give yourself away.

I can’t say for sure whether it was during this period that he developed his fluency in Malapropisms. He often said that he’d like a “murial” painted on the back wall of the house, and in recent years, before COVID eclipsed it as a topic of conversation, he liked to discuss what he always referred to as Bretix.

Despite earning his living with numbers, at school literature was his love, poetry in particular. He always included a few lines of poetry in mum’s birthday cards, some penned by himself – a cause for much sniggering for us as children growing up, and in later years something to bring a lump to the back of the throat – and which leads me nicely into his lifelong raison d’être – family.

Although Frank and Doreen had known each other since they were both fifteen, they didn’t start dating until they were twenty, and they were married on 7 February 1959. Easter came early that year, and it was a bitterly cold day at the beginning of lent, the church a somewhat cheerless place stripped of flowers. Except back then it wasn’t about show and the photographs, and what had started out as a slow burn lasted for the next sixty-three and a half years together.

Mum had never been much of a drinker, and it amused her sisters no end that she got hitched to an Irishman who liked his beer, their view vindicated at the wedding when the bride and groom were called for the first dance and Frank had to be fetched out of the bar.

I was born in December of that same year, followed by Vince in June 1961 and John in February ’66, the genes coming through strongly, three boys for the middle son out of three boys, and a handful for mum, although personally I can’t believe it was that bad.

Grandchildren came along in due course, Gabriella, James and Bethany. Frank doted on them all, still fit enough for wheelbarrow rides up and down his deceptively-steep garden. He lived long enough to enjoy three great-grandchildren, Riley, Alex and Tommy, all of whom he loved dearly, even if the wheelbarrow rides were a thing of the past.

While mum was busy smacking the children, Frank had made the jump from Dagenham to the City. His father Pat worked as a sheet metal worker in Fords, where he’d identified early on that the accountants sat around in the office all day with their feet on the desk – what better recommendation could a father give his son?

Except if you knew Frank, you know how far off-base that was. Still working almost to the day he died, the consummate professionalism that characterized his working life unwavering, as was his commitment to keeping himself up to date. One of the many tasks to be dealt with now that he’s gone will be to cancel his subscription to Tolley’s Tax Data – unless there’s anyone in the congregation who’d like to take it over – a right riveting read it isn’t.

Almost seventy years earlier, he joined the accounting firm Woodington Bubb at a salary of thirty shillings per week, and from there moved to Jenkins Wood, paying the princely sum of £2 – an improvement over the situation that had existed not many earlier when articled clerks received no salary at all. Studying for the Chartered Accountant’s exams was by correspondence course, and in his own time. Mum remembers calling at Frank’s house to go out for the evening and having to wait while he finished his studies, passing the time chatting to Frank’s father, Pat, hoping she smiled and nodded in all the right places, not understanding a word of it on account of his still-strong Belfast accent.

Frank qualified as a Chartered Accountant in March 1960. Back then, the City was a very different place, still the preserve of the old school tie network, although change was in the air. At one firm looking to leave behind the public-school practice of calling one another by surname only, a partner told him that going forward Frank should call him Vivian, much to Frank’s amusement – boys from Dagenham didn’t know any men called Vivian.

He spent a number of years in public practice in the City and West End, before moving into teaching. He started at Chelmsford College and from there moved to the City of London Polytechnic on Moorgate, lecturing on accounting and taxation. At the same time, he set up his own practice with one employee to type correspondence – when she wasn’t cooking our dinner. Through the patronage of James Walsh, the owner of the Catholic Times and a very big cheese in the lay Catholic hierarchy, Frank acquired many Catholic client organizations, the biggest of which being Douai Abbey and School, a client much larger and more prestigious than a one-man band would ever normally aspire to, but one that he kept for more than thirty years.

Hard work necessarily demands a release. Since we’re talking about Frank, beer comes to mind. He searched out a local wherever he lived, the Beehive and then the KG5 in Ilford, and latterly the Victoria Tavern in Loughton. He made good friends in them all, and a number of his chums from the Vic are here today, all of whom were so very kind and especially supportive during his illness, proof as if any were needed, of what a great institution the English pub is, a sentiment with which Frank would wholeheartedly agree.

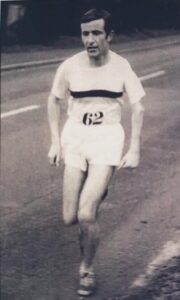

Of course, you’ve got to earn your beer, do something to get a thirst going, and so we come to running, or more accurately, training, because it was always with the next race in mind.

Frank joined Ilford AC in the late fifties, and quickly became an active member of the club’s running and après-run community.

In 1959, he made the Ilford 12-man team for the London to Brighton relay, no mean feat as competition for a place was fierce. He ran the short leg from Redhill to Horley with distinction, the medal for most improved team which Ilford won that year his proudest athletic possession.

He ran in the 1963 Southern Cross-Country championships at Parliament Hill, the year of the big freeze. Frank allegedly appeared in a large photo in the Sunday Mirror of runners hacking through the snow under the headline “Nothing stops the iron men!” – not unjustified in those conditions.

In later years, his sons were inducted – or is it abducted – into the sport. Vince has many memories of being put out of the car at the side of the road on the way home from a race so that Frank and his partner in crime, Mick Herring, could make it back to the Joker in Seven Kings in time for doors opening at 5:30. Although at times directionally challenged, often getting lost on the way to a race, when it came to getting back to the Joker, he did a great impersonation of a thirsty homing pigeon.

In a similar vein, after collapsing at the end of a ten-mile road race, I remember being told of Frank’s immediate reaction – not “is he okay?” but “Doreen’s gonna kill me”. Worse, they didn’t make it back to the Joker at all that night, something Mick has held against me ever since.

John went a different route, into triathlons. Frank was there for his first race in Marlow, a self-appointed additional marshal on the running leg shouting traditional Frank-style encouragement to not only John but all the competitors – “start trying now” or “come on, it’s only pain.”

He also lent his name to a style of cross-country run – a Frank Heaney run – the essential ingredients of which are brambles, stinging nettles and whatever inflammation-inducing crops the farmers are growing that year – with no discernible path through them – the resulting bleeding, itching legs evidence of a Saturday afternoon well spent.

In addition to running, Frank enjoyed travelling. He loved France, despite it being full of the French, with its vineyards and laid-back way of life reminiscent of what has been lost in England, and in particular the hotel at Mailly-le-Château on the River Yonne. There, Monsieur et Madame ’Eeeney were treated as celebrities, motoring down year after year in their Panther Lima open-top sportscar, true to the traditions of the age of elegant travel – but still finding time to don running shoes and pound the dusty French lanes.

Frank liked an anecdote, and this eulogy contained far more of them than it did facts. But in case any of you oldies have been snoozing, let me say it plainly: he was a man who never complained; he as good as defined the concept of an optimist; his generosity knew no limits, but most of all, to quote mum, his wife of more than sixty years, his lovely girl, on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary bash: he’s the kindest man I ever knew.